NOTICE

Persons attempting to find a motive in this narrative will be prosecuted;

persons attempting to find a moral in it will be banished;

persons attempting to find a plot in it will be shot.

By Order Of The Author,

Per G.G., Chief of Ordnance.

— Mark Twain, Author’s Note for The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

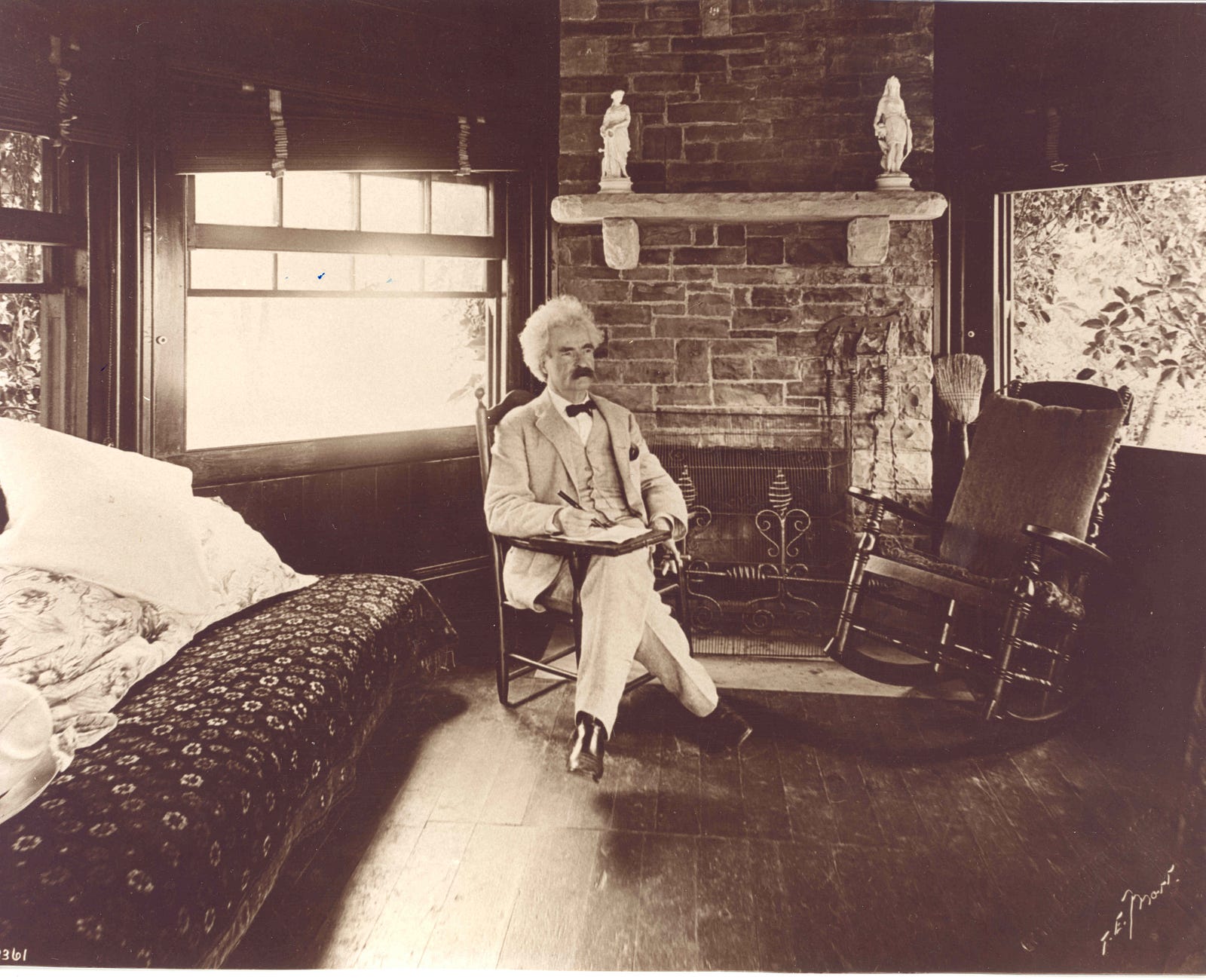

Mark Twain, undoubtedly writing an angry screed much like this one

Note: There will be spoilers for The Beginner’s Guide herein; if you care about that sort of thing you should probably play it before you read this.

The Beginner’s Guide opens with the narrator introducing himself as Davey Wreden, the creator of The Stanley Parable, explaining that he is going to talk about some games created by a friend named Coda and how Coda’s games had inspired and guided him in his own efforts as a designer. He expresses the hope that by sharing these games he will encourage Coda to go back to making games, as he seems to have made his last game in 2011. As he began to explain the first level, I admit that my first reaction was intensely hostile.

“Don’t you explain this game to me,” I thought.

“It’s a reminder that this video game was constructed by a real person,” he says. The strange thing here is that Davey Wreden the narrator is asserting that these games were created by Coda, who we have no reason to believe is real, and were, in fact, created by the real Davey Wreden as if he were the fictional Coda to then be narrated by a fictionalized Davey Wreden. (Are you confused yet? I don’t blame you.)

“What was going through his head as he was building this?” Narrator Davey asks. And I think “why don’t you just ask him?” No one can know what’s going on inside another person’s head without asking, but Davey barrels on, because he’s going to explain it to us anyway.

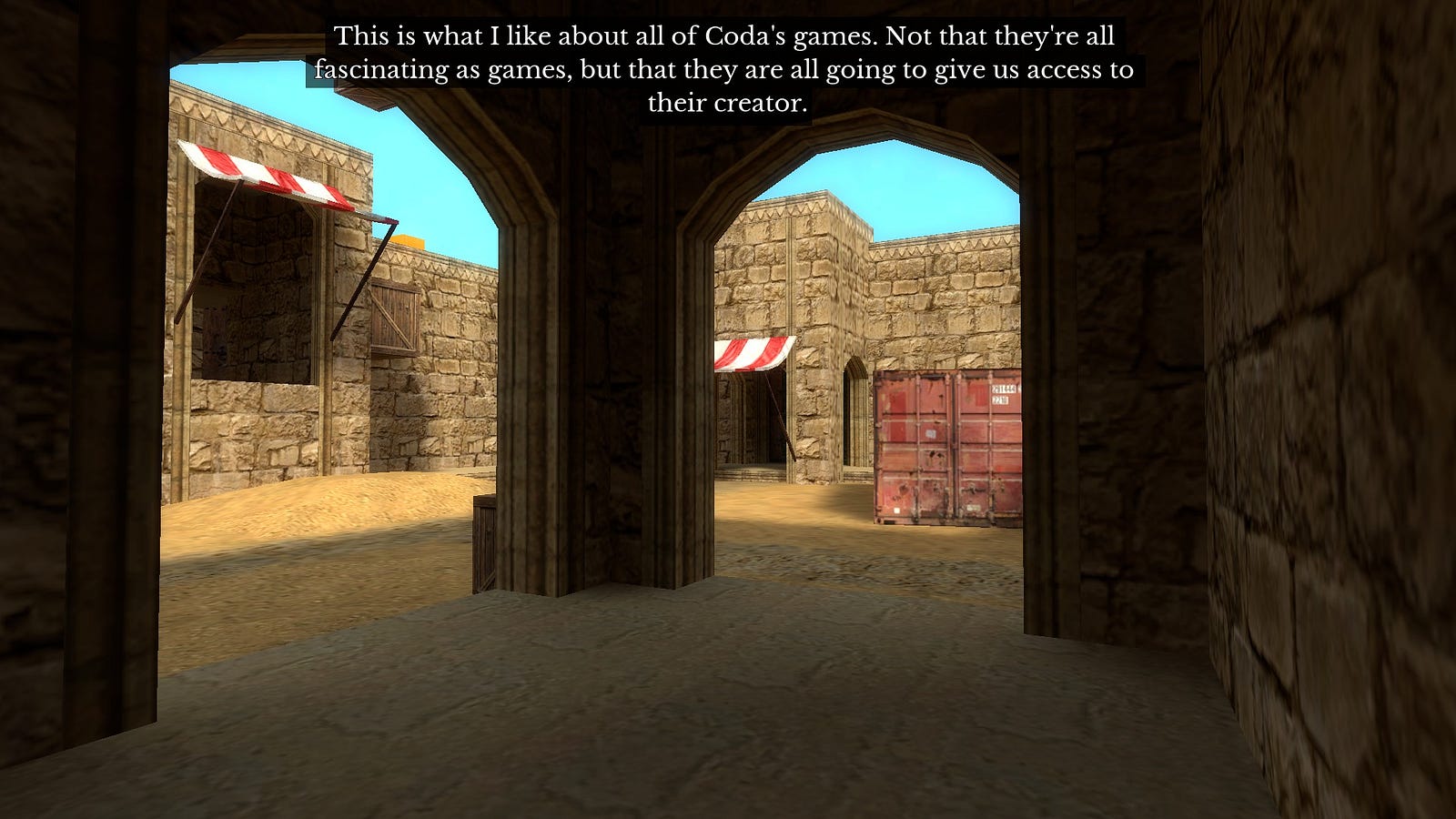

“This is what I like about all of Coda’s games. Not that they’re all fascinating as games, but that they are all going to give us access to their creator… I want to get to know who this human being is,” he continues.

This robot has a warning for you

Already my brain is screaming “Alert Alert Alert” at me.

This is where I’m going to stop quoting the game at you, or else I could easily end up going through and ranting about nearly every line in it, because I absolutely loathed the narrator.

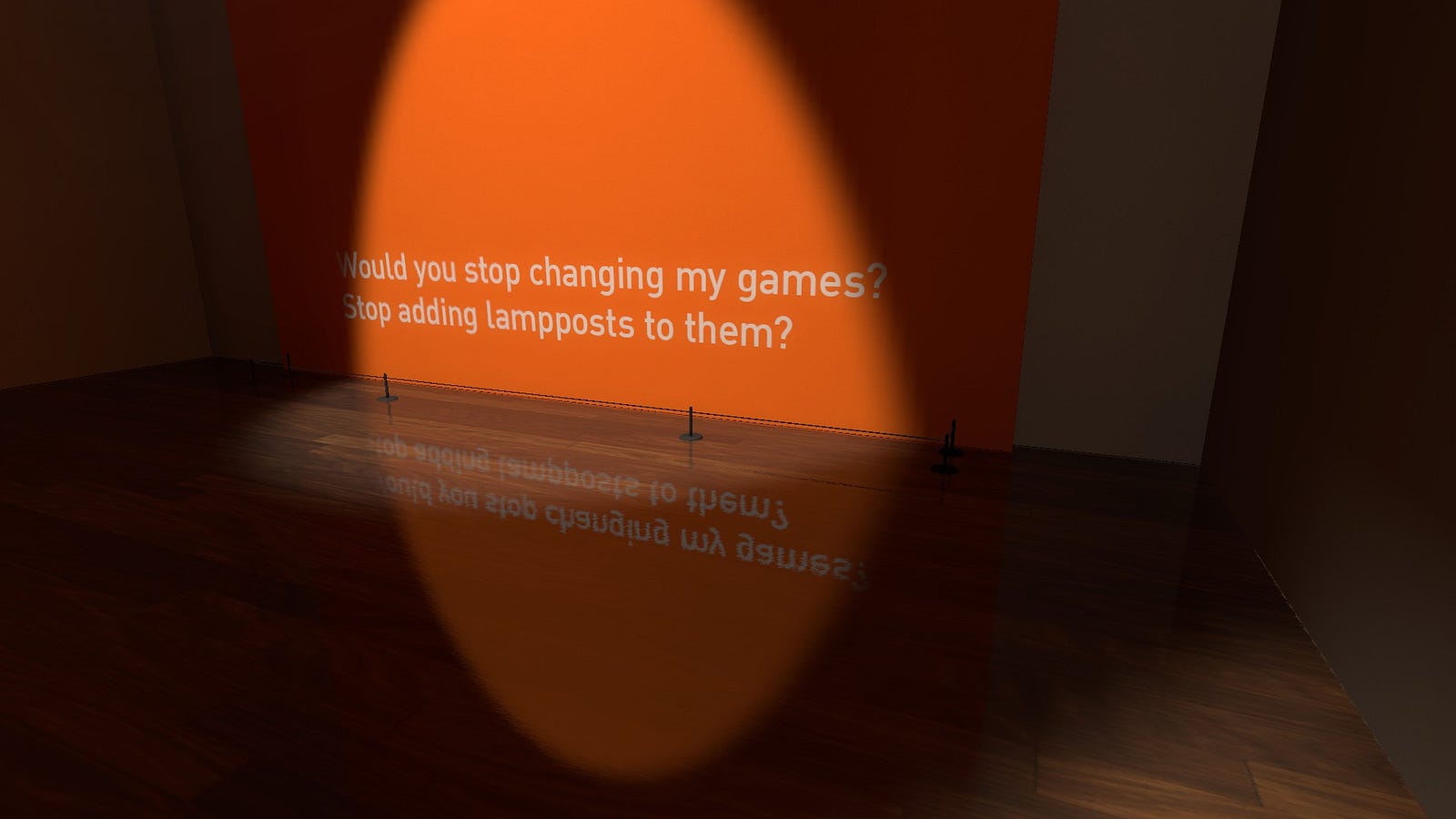

I felt like I was playing a game narrated by this lady

I don’t think this means the game is a failure, and it’s been interesting to me reading the various perspectives on the game and what it means. I particularly recommend these pieces by Laura Mandanas, Cara Ellison, Laura Hudson, Cameron Kunzelman and Brendan Keogh. There is definitely something to be said about a game that provokes so many thoughtful pieces by so many great writers.

I do think there are a couple of questions that, depending on your answer, inform how you understand The Beginner’s Guide and what you think it’s trying to say:

- Is Davey Wreden really narrating as himself or is he a stand-in for someone else?

- Is Coda a real person?

- As a player, do you identify with Coda or with Davey or are you seeing it from another point of view?

From the start I identified with Coda.

I assumed that Coda is the “real” Davey and that Narrator Davey is a stand-in for the audience; the audience being us, the players, as well as the critics and the larger audience for games in general. I tend to think that perhaps Narrator Davey is Wreden’s attempt to understand the entitlement that fans feel towards creators, though I’m hesitant to speculate too much on Wreden’s perspective (especially considering as the game itself exists as a warning about the perils of doing so).

Narrator Davey asserts that we can know Coda through his games; at the same time Davey alters Coda’s games to meet his own standards for making them playable. Eventually we learn that he hasn’t restricted himself to alterations allowing the player to progress in ways not permitted in their original state, but he’s also altered them in other ways, as well as showing them to people without Coda’s consent. We’re not seeing Coda’s games the way he intended them to be seen (which is basically not at all – not by us, anyway) or in anything resembling their original state; in fact, we have no way of really knowing how much the games represent Coda’s original vision for them at all. Additionally, there is a problem with thinking that playing someone’s games, even extremely personal ones, really tells you something about that person’s emotional state or personality or perspective. Even an extremely personal game can never be more than a snapshot of one aspect of a person’s emotional state or perspective.

I know this because most of the games I’ve made so far have been personal in some way. I also know that I am the only person who really knows to what extent they are my own perspectives and experiences and to what extent they are manufactured for the sake of the experience I want to create. There are things I want my games to tell you, but those things are not so much about me but about the world the way I see it and the things I think are important to communicate in a game.

I can tell you that in Final Girls, some of the events and dialogue are fictionalized versions of things that I’ve experienced, and that love/space is based in part on a dream I once had. Epilogue is probably the most personal game that I have written (and for a long time I didn’t intend to share it publicly at all) but even that is only a snapshot. Every single one of my games contains a seed of my own experiences, whether I intend it to or not. My telling you that still doesn’t inform you as to how much of my games is based in my real life and experiences and how much is fiction. I prefer to keep it that way. I would hope that the things I create speak for themselves, and I would hope that my audience understands that playing them doesn’t really enable them to know me the way my friends and family do. The only way to get to know someone is to get to know them, and I don’t think obsessively consuming and poring over their work is going to do that. For one thing, it’s a one-sided relationship — you see only what the creator puts out there and they know nothing of you. It’s not really a conversation, no matter how much you might wish it were.

I think there is also an issue that creators and celebrities where their audience can be so attached to their work that they feel a kind of intimacy and attachment to them as well as their work. This can sometimes lead to a sense of entitlement and an expectation that we will continue to provide exactly the same things to our audience that drew them to us in the first place. There is a sense that somehow the act of creating carries with it an obligation to continue creating and to do so in a way that meets some external requirements of our audience.

This notion is deeply troubling to me.

I think the other reason I had such a strong negative reaction to The Beginner’s Guide is the way I felt like it connected to my experiences as a woman working in games. In some ways, the game feels like Men Explain Things to Me in the form of a video game. The narrator is explaining Coda’s games and what they say about Coda; I have had this experience not only with men explaining other people’s games to me but even my own games. Whenever I talk to men about games I’m working on or ideas I have, very often I get suggestions about how I should “improve” them, often from people who have never worked in games, never made games before and wouldn’t have the first clue of where to start.

There is also a tremendous sense of violation upon learning that Narrator Davey had shared Coda’s games without permission, even altered them to his own liking (with no real way to know the extent of the alterations — we have only Davey’s word for it, and there are indications that he is quite the unreliable narrator) and I was again reminded of the many times that men have violated my boundaries with regard to communication and physical space and privacy, as well as the many times that male coworkers have presented my ideas as their own and gotten credit for my work. I felt like I was being forced into intimacy with a stalker and pushed to try and sympathize with him, and instead I just felt angry and violated again.

I wonder if maybe that was the point of it, maybe it would help other men experience some of what I feel? Part of me wants to agree with the read in this piece by Laura Mandanas on Autostraddle:

“For me, the most relatable parts of the broader game were actually scenarios that made me think of gendered experiences I’ve had in the professional world… Now, I know the feeling doesn’t really come across in written text, but there’s something about the tone of Davey’s voice and the pauses in his cadence on the audio track that really get to me. To my ears, it sounds like the creepy dude at the bar who keeps pestering a girl until he gets slapped, then sheepishly returns to his friends and selectively glosses over the details as he explains what went down.”

It occurs to me is that this is one of those areas where men’s experiences moves closer to women’s experiences with male entitlement — when dealing with celebrity and a creator’s relationship to their audience. This isn’t to say that male creators deal with the same level or intensity of entitlement and harassment that female creators do, but rather that male creators have some experiences with it that are closer to the average woman’s experience of daily life. Male creators face stalkers and harassment, which are sadly things that women who are not at all famous deal with regularly.

“I’m your number one fan”

For example, in Stephen King’s Misery, Annie Wilkes is an obsessed fan who shows up to force the writer Paul Sheldon to write another book for her. She says: “God came to me last night and told me your purpose for being here. I am going to help you write a new book.” (Interestingly, many of King’s fans took the book to be an indictment of them and were really angry that he could write something so critical of the people who supported him by buying his books. More on that here.)

Davey Wreden, in The Beginner’s Guide, packages Coda’s games in an attempt to force him to create more games.

“That’s why I’m releasing this collection of your work, is because I haven’t been able to find any other way to reach you. I’ve tried everything. And… so a part of me has hope, that if I put this compilation out into the world, and if I put my name on it, that maybe enough people will play it so that it will find its way to you, so I can tell you that… I’m sorry. I know I screwed up. If I apologize to you truly and deeply, will you start making games again? Please, I need to feel OK with myself again, and I always felt OK as long as I had your work to see myself in.”

He’s apologizing while doing the very thing he’s apologizing for, sharing and altering Coda’s games. His apology is there only in an attempt to get Coda to continue doing what Davey wants him to do, which is to make more games. The thing is, we don’t actually know that Coda’s stopped making games, or if he has, why. We only know that he’s stopped sharing his games where Davey has access to them. And why wouldn’t he? Wouldn’t you, if you could, stop an entitled and obsessive fan from having access to your work (and any other aspect of your life)? And let’s be very clear here: Narrator Davey is a stalker. He’s repeatedly violated Coda’s privacy and express wishes by sharing his games and making alterations to them.

Let me also be clear that when I say “Narrator Davey is a stalker” I mean just that. This is a character in a game named after the very real creator of said game, but unlike Narrator Davey, I’m not going to make assumptions about what the game says about Davey Wreden. It’s impossible to know that and mostly futile to speculate about it. The importance of a work is what it says about itself and about the world, and less about what it says about its creator. Especially since the only way to know what is true for its creator is what he tells us.

The final question I keep coming back to is, why the name? What is it a beginner’s guide for? It could be the beginner’s guide to Coda’s games, but it’s implied that nearly all of Coda’s games to date are included in the collection, so that would make it more of a comprehensive guide than a beginner’s guide.

I think it’s a beginner’s guide because it’s a novice mistake to think that in interpreting a work we understand it and by extension, understand the creator. Once you’re past the beginner’s guide, one would hope that you recognize that a work speaks to its own meaning and doesn’t open a window into the creator’s soul. One would hope that you learn to recognize that creators are people with the right to share their work, or not, to be as private as they need or desire to be.

As a creator, I decide when to grant you access to my work, and granting you access to my work does not give you access to me, as an individual.

Originally published on Medium.